Giants carved into the old Egyptian mysteries

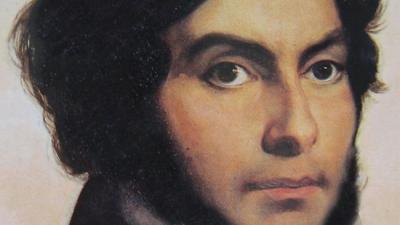

TODAY is a double anniversary for Egyptology. On this day 220 years ago, French scholar Jean Francois Champollion, who played a major part in deciphering ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, was born. It is also the bicentenary of the birth of Karl Richard Lepsius, a Prussian archeologist who built on Champollion's research into the ancient writing system, making his own discoveries.

Champollion was born on December 23, 1790, at Figeac in France. His parents lacked money to send their youngest of seven children (two of whom died in infancy) to school so he was mostly educated at home until, at nine or 10, he went to study at the Lycee at Grenoble. There he came under the influence of Jean Baptiste Joseph Fourier, the great mathematician, who had been in Egypt with Napoleon and had made a study of ancient Egypt.

Fourier was there when a large piece of granite inscribed with hieroglyphs, Egyptian demotic script and ancient Greek was found in 1799. The granite block was later called the Rosetta Stone.

Under Fourier's tutelage, Champollion developed an interest in Egyptology and eastern languages. By age 16 he had mastered Greek and Latin along with Persian, Ethiopian, Sanskrit, Zend, Pahlevi and Arabic. At age 19 Champollion became a professor at the Lycee in Grenoble.

He learned of the work of Thomas Young, the British researcher trying to fathom the writings on the Rosetta Stone. By 1814 Young had deciphered much of the demotic text but was making slow progress on the hieroglyphs. Left without a teaching post when the letters faculty at Grenoble was closed in 1815, Champollion set his mind on deciphering the ancient words.

By 1822 he was publishing papers on translation of the hieroglyphs and he began work on a guide to Egyptian grammar and vocabulary. He joined trips to Egypt and held museum and teaching postings but died suddenly in 1832 while working on his book. His incomplete Grammaire Egyptienne Egyptian dictionary was published in 1836.

By then a new scholar was entering hieroglyphics - Lepsius. Born in Naumburg an der Saale, Saxony, on December 23, 1810, he studied archeology and archeological philology at Leipzig, Gottingen and Berlin and became an early follower of Champollion. When Champollion's dictionary was published in 1836 it was derided by many but Lepsius was one of its early supporters.

He identified areas where Champollion went wrong. In 1842 Fredrick Wilhelm IV of Prussia commissioned Lepsius to lead an expedition to Egypt to conduct some of the first truly scientific studies of the pyramids and other ancient structures. His team identified and documented hundreds of pyramids, burial chambers and monuments, measured the Valley of the Kings, gathered evidence that would reveal the character of Akhenaton and collected thousands of artefacts. Many of his books on Egyptian monuments, lists of kings and the chronology of ancient Egypt would be texts for Egyptologists well into the 20th century.

While we might be horrified today by the number of items taken away to be housed in German archives, as well as reports of him carving the name of his patron Fredrick Wilhelm into the stones above the entrance to a pyramid, Lepsius saved many artefacts from less principled treasure hunters. Many of the well preserved Egyptian objects in the collection of the Berlin Museum are there thanks to Lepsius. He also contributed greatly to a broader knowledge of Egyptian history.

In 1866 he led another expedition on which he discovered the Decree of Canopus, a stone monument dating back to 238BC, with hieroglyphic, demotic and Greek scripts. It helped to verify some of the findings from the Rosetta Stone.

Lepsius made a final visit to Egypt in 1869 to see the opening of the Suez Canal, after which he was director of the Royal Library in Berlin in 1873. He died in 1884.

Source: The Daily Telegraph, 23/12/10

- Συνδεθείτε για να υποβάλετε σχόλια

Εκτυπώσιμη μορφή

Εκτυπώσιμη μορφή- Send by email